Three weeks ago I took a leave from my day job as a Lean-Agile consultant to finish my doctoral dissertation in three months. The last time I did research full-time I was working at Aalto University SimLab from May 2013 to December 2015. Based on this, you might think I had this whole “how to do research” under wraps, but I was always unsatisfied about how use my time effectively and actually write the dissertation. But now after a year as a Lean-Agile coach I felt more prepared to tackle the challenge than ever before.

This is a retroperspective on how I’ve managed to make myself a better researcher and enhance my probability of getting the dissertation done by July. In this part 1, I will give you an overview into some techniques and tools that I’ve created in the last three months leading up to and the beginning of my writing leave. In part 2, I will explain more about how I actually use the system formed by these tools.

Thinking about work items

When thinking about a big project, even one where a lot of thinking and creativity are needed, it helps me to accept that everything is just work that needs to be done. This comes across in both Lean and Agile and it applies to assembly lines where the machines are literally just waiting for you to assemble them, but also software engineering where we track our progress based on the system functionalities we have delivered. You can have work items of different types and sizes, but each item of work is always either not started, in some state of work-in-progress (WIP), or done. Sometimes pieces of work need to be iterated, but the new iteration is thought of as a new item of work.

Breaking down large chunks of work

The biggest lesson I learned from working in an agile team was that the size of the work items you handle matters. Agile teams work with work items called Stories that can be completed within two weeks, i.e. a Sprint, and Lean teams just want to keep item sizes small and consistent. By the time it is finished, my doctoral dissertation will have taken me 3½ years, over 10% of my life. If that is not a work item that needs breaking down, I don’t know what is.

When I look at my work as an individual, my biggest item of work should be roughly half a day. This means that if I work on an item for half a day (e.g. the whole morning), I am reasonably confident that I will get it done. If a job has multiple phases, I might try to break it down as small pieces as I can just so I have more focus and flexibility during the day. Work item size might be the most important thing on this list, which will make even more sense when we start talking about iterations and limiting work-in-progress.

Different areas of work

I started by creating categories of work based on the end result – the dissertation text itself and its chapters. Each chapter. Writing a dissertation or any kind of thesis is hard because you can’t just sit down and write it, you need to write multiple chapters in parallel because your view on the literature changes how you analyze your data and the conclusions will place requirements on how you frame your research in the introduction and so on. Each chapter will also need a different kind of mind set, whether it’s talking to a large audience in the introduction, reading and commenting on literature or working with data in analysis.

Now if I plan to do a revision that will impact multiple chapters, I can write down work items to each chapter and then focus on one chapter at a time instead of jumping wildly from one chapter to another. Having a system in place for tracking which chapter each work item will impact also helped me talk with my supervisors. When talking about the dissertation and giving feedback, we are always talking about the state of this or that chapter, so this system helps me to both describe how I have developed each chapter and create work items based on the feedback of that chapter.

Focus on the desired state

When starting an agile way of working, a lot of people have problems internalizing that the best way to write down work items is not “do thing X” but rather “X is done”, or even better, “Y can X”. For example, my work item for analysis reads “Episodes have been searched and listed from the transcription”. The difference from “Search and list episodes from the transcription” is subtle at first, but reading the former automatically triggers a response of “What still remains to do?” which helps me get that work item into Done and on to the next instead of evading a vague work item because I’m not really sure what to do next.

Visualizations for everything

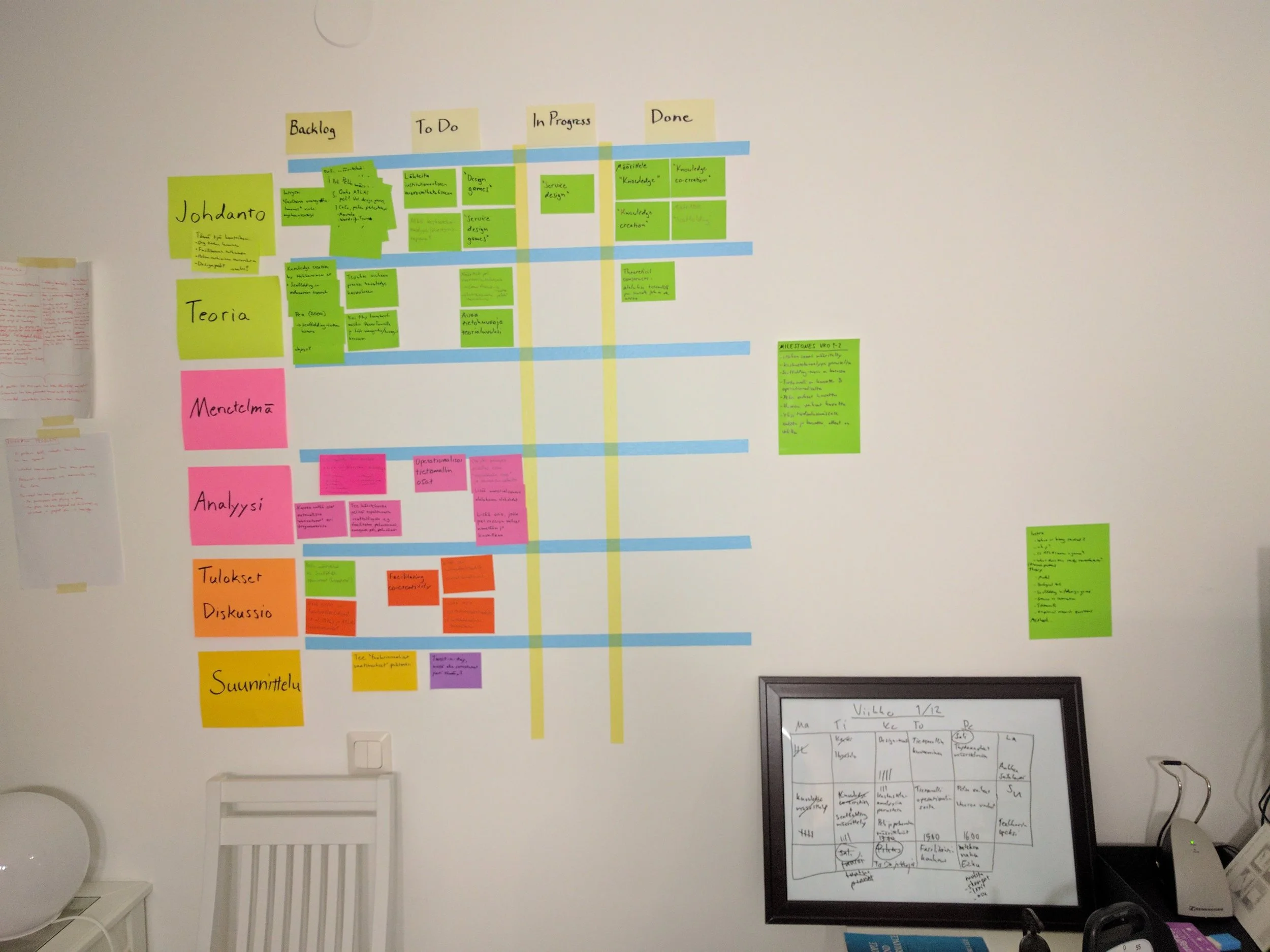

Most of my work revolves around three objects I have on the wall next to my monitor. My Kanban wall, my weekly calendar and my weekly objectives:

The big mess of tape and magnetic notes is my Kanban wall. The columns tell which phase each work item is in. I often have just a mess of things I might do on the left – called a Backlog – which is then refined into things waiting to be done under “To Do”. I only allow one item of work to be “In Progress” at a time so I know what I’m currently doing – this is called a WIP limit and it helps me finish work items before I move on to the next. The rows are the different chapters: Introduction, Theory, Method, Analysis, Results & Discussion, and then one for planning and other general work like “remember to tweet a lot”.

The brown framed whiteboard is my weekly calendar that I update at the start of every week. I plan my daily work time in two chunks - morning and afternoon – and mark down what I expect to finish during that time. I also mark down everything else that impacts my available work time e.g. meetings, gym, rest days or the time I must leave to catch a bus to meet my friends. During the week, I tally the number of 25-minute timeboxes that I get done, with breaks between them for stretching and snacking. This gives me a sense of how well I’m able to keep to my writing routines and creates a bit of accountability so I have a better chance of reaching my goals.

The two big magnetic notes above the weekly calendar are weekly objectives. I initially did my objectives for two weeks i.e. Sprints, but quickly realized that I had to have objectives that fit my cadence (more on that later). They’re not (always) replications of the work items, but instead they’re usually things I’ve agreed with my supervisor to do in the following weeks. After settling down with the objectives, I can then identify which chapters need work items and how to write them in an actionable way.

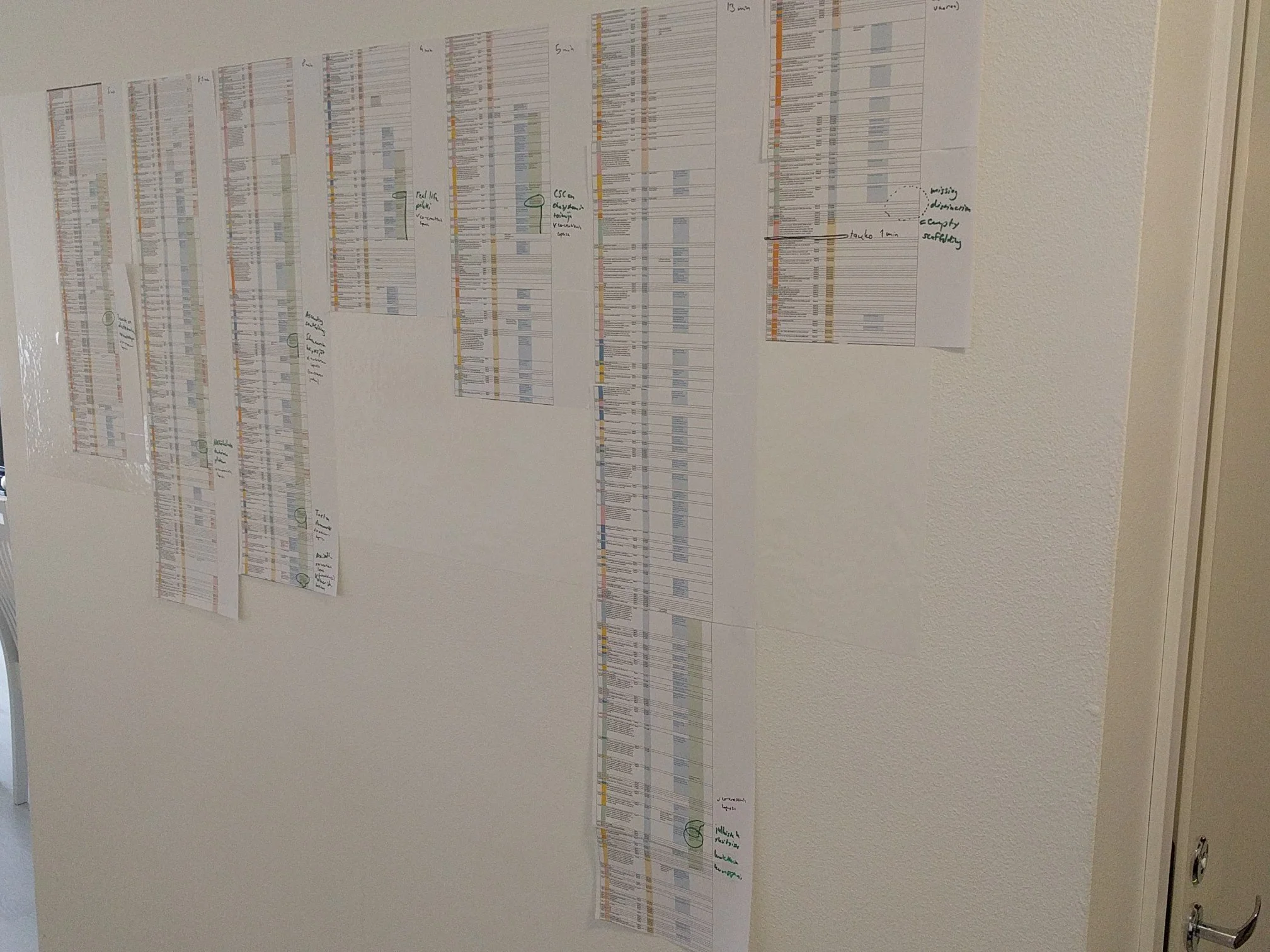

Finally, I use wall space for all kinds of notes and data analysis. Because I don’t have a whiteboard at home, I use Magic Chart, a roll of whiteboard paper that sticks to your walls. They are handy for theory formulation and data analysis, and they can easily be moved around or trashed after they’ve been incorporated into the text.

That’s all for today, follow me on Twitter to get a heads-up on Part 2: Making it all come together.