I wrote a thing for the Joint Futures conference blog by employer Nitor is sponsoring. Check it out!

Can research be agile? (Part 1)

Three weeks ago I took a leave from my day job as a Lean-Agile consultant to finish my doctoral dissertation in three months. The last time I did research full-time I was working at Aalto University SimLab from May 2013 to December 2015. Based on this, you might think I had this whole “how to do research” under wraps, but I was always unsatisfied about how use my time effectively and actually write the dissertation. But now after a year as a Lean-Agile coach I felt more prepared to tackle the challenge than ever before.

This is a retroperspective on how I’ve managed to make myself a better researcher and enhance my probability of getting the dissertation done by July. In this part 1, I will give you an overview into some techniques and tools that I’ve created in the last three months leading up to and the beginning of my writing leave. In part 2, I will explain more about how I actually use the system formed by these tools.

Thinking about work items

When thinking about a big project, even one where a lot of thinking and creativity are needed, it helps me to accept that everything is just work that needs to be done. This comes across in both Lean and Agile and it applies to assembly lines where the machines are literally just waiting for you to assemble them, but also software engineering where we track our progress based on the system functionalities we have delivered. You can have work items of different types and sizes, but each item of work is always either not started, in some state of work-in-progress (WIP), or done. Sometimes pieces of work need to be iterated, but the new iteration is thought of as a new item of work.

Breaking down large chunks of work

The biggest lesson I learned from working in an agile team was that the size of the work items you handle matters. Agile teams work with work items called Stories that can be completed within two weeks, i.e. a Sprint, and Lean teams just want to keep item sizes small and consistent. By the time it is finished, my doctoral dissertation will have taken me 3½ years, over 10% of my life. If that is not a work item that needs breaking down, I don’t know what is.

When I look at my work as an individual, my biggest item of work should be roughly half a day. This means that if I work on an item for half a day (e.g. the whole morning), I am reasonably confident that I will get it done. If a job has multiple phases, I might try to break it down as small pieces as I can just so I have more focus and flexibility during the day. Work item size might be the most important thing on this list, which will make even more sense when we start talking about iterations and limiting work-in-progress.

Different areas of work

I started by creating categories of work based on the end result – the dissertation text itself and its chapters. Each chapter. Writing a dissertation or any kind of thesis is hard because you can’t just sit down and write it, you need to write multiple chapters in parallel because your view on the literature changes how you analyze your data and the conclusions will place requirements on how you frame your research in the introduction and so on. Each chapter will also need a different kind of mind set, whether it’s talking to a large audience in the introduction, reading and commenting on literature or working with data in analysis.

Now if I plan to do a revision that will impact multiple chapters, I can write down work items to each chapter and then focus on one chapter at a time instead of jumping wildly from one chapter to another. Having a system in place for tracking which chapter each work item will impact also helped me talk with my supervisors. When talking about the dissertation and giving feedback, we are always talking about the state of this or that chapter, so this system helps me to both describe how I have developed each chapter and create work items based on the feedback of that chapter.

Focus on the desired state

When starting an agile way of working, a lot of people have problems internalizing that the best way to write down work items is not “do thing X” but rather “X is done”, or even better, “Y can X”. For example, my work item for analysis reads “Episodes have been searched and listed from the transcription”. The difference from “Search and list episodes from the transcription” is subtle at first, but reading the former automatically triggers a response of “What still remains to do?” which helps me get that work item into Done and on to the next instead of evading a vague work item because I’m not really sure what to do next.

Visualizations for everything

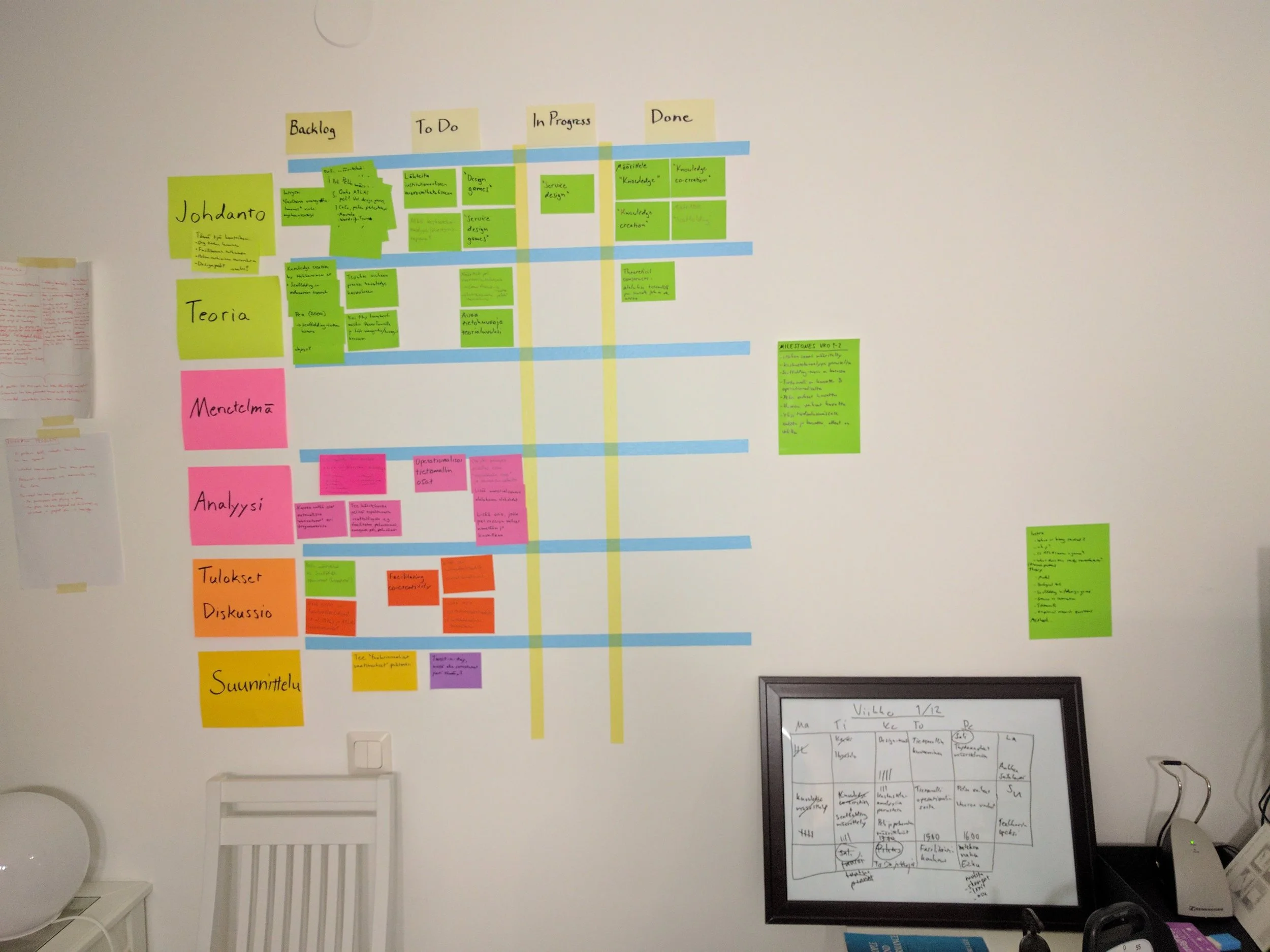

Most of my work revolves around three objects I have on the wall next to my monitor. My Kanban wall, my weekly calendar and my weekly objectives:

The big mess of tape and magnetic notes is my Kanban wall. The columns tell which phase each work item is in. I often have just a mess of things I might do on the left – called a Backlog – which is then refined into things waiting to be done under “To Do”. I only allow one item of work to be “In Progress” at a time so I know what I’m currently doing – this is called a WIP limit and it helps me finish work items before I move on to the next. The rows are the different chapters: Introduction, Theory, Method, Analysis, Results & Discussion, and then one for planning and other general work like “remember to tweet a lot”.

The brown framed whiteboard is my weekly calendar that I update at the start of every week. I plan my daily work time in two chunks - morning and afternoon – and mark down what I expect to finish during that time. I also mark down everything else that impacts my available work time e.g. meetings, gym, rest days or the time I must leave to catch a bus to meet my friends. During the week, I tally the number of 25-minute timeboxes that I get done, with breaks between them for stretching and snacking. This gives me a sense of how well I’m able to keep to my writing routines and creates a bit of accountability so I have a better chance of reaching my goals.

The two big magnetic notes above the weekly calendar are weekly objectives. I initially did my objectives for two weeks i.e. Sprints, but quickly realized that I had to have objectives that fit my cadence (more on that later). They’re not (always) replications of the work items, but instead they’re usually things I’ve agreed with my supervisor to do in the following weeks. After settling down with the objectives, I can then identify which chapters need work items and how to write them in an actionable way.

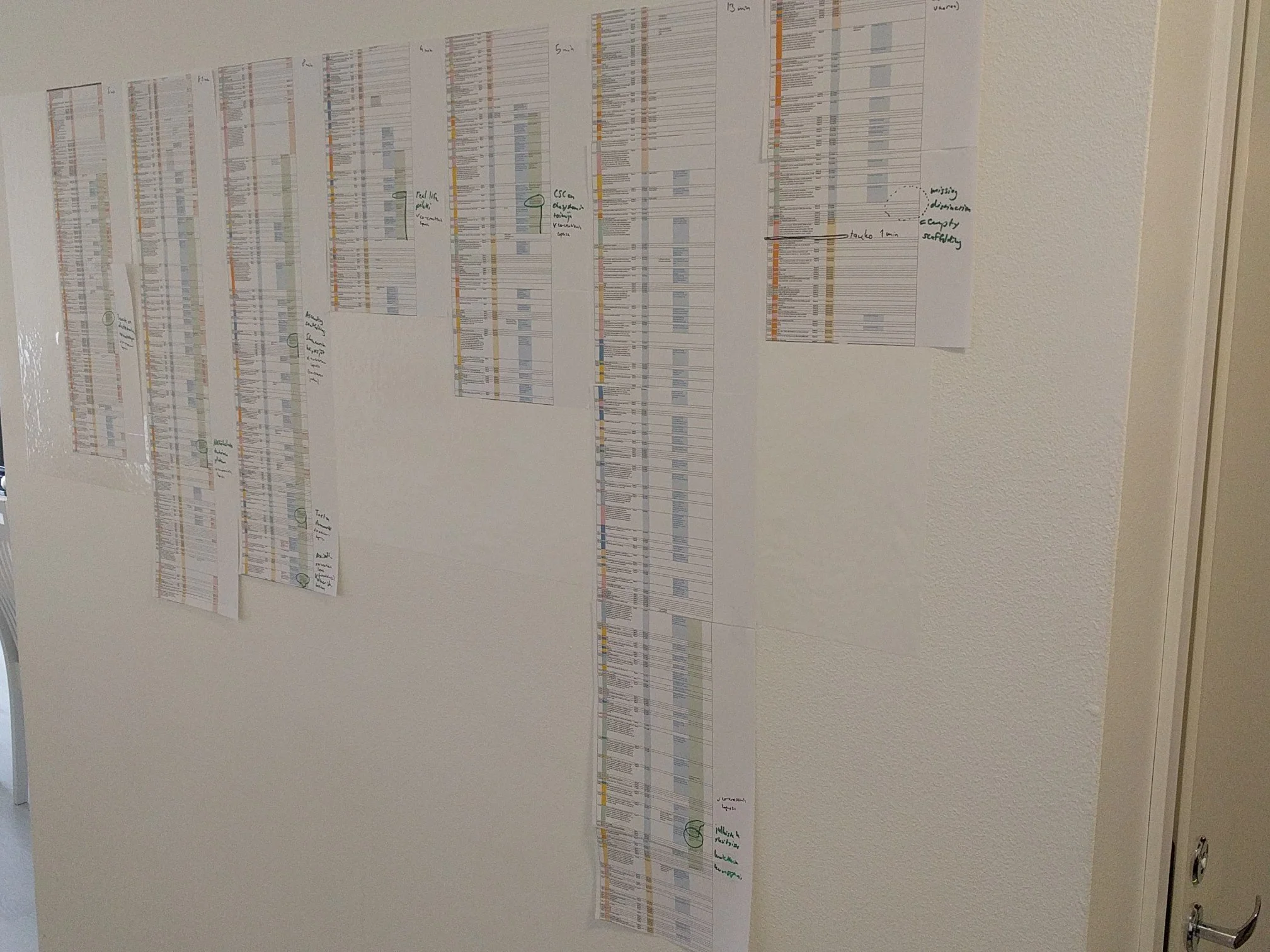

Finally, I use wall space for all kinds of notes and data analysis. Because I don’t have a whiteboard at home, I use Magic Chart, a roll of whiteboard paper that sticks to your walls. They are handy for theory formulation and data analysis, and they can easily be moved around or trashed after they’ve been incorporated into the text.

That’s all for today, follow me on Twitter to get a heads-up on Part 2: Making it all come together.

People over principles

The last month of my life has been a nosedive into the Scaled Agile Framework, i.e. SAFe, as a new member of the Nitor Delta team. I admit, I was initially suspicious of a systems-thinking heavy framework that gets sold to executives and managers alongside slogans like "only managers can change the system" and "leadership is imparting excellence into the organization".

But the best way to approach SAFe is through the SAFe principles: a list of nine principles which act as a kind of step-by-step logical induction of the Lean-Agile philosophy that underpins SAFe. Through them, I was convinced that correctly applied SAFe is not a tool of control but liberation, and I'm happy to share with you how I came to that conclusion. Below are the nine SAFe principles rewritten to emphasize their ability to distribute authority and agency in your organization.

1. Use a shared measurement of success

In order to be sustainable and beneficial, everything a business does should be guided by the creation of value in the most effective way. This simple idea should be present in everything an organization strives for: which user pains do we address, when do we launch, how do we organize customer support? An economic view that runs through a system empowers actors to make their case across functions and roles at all levels of an organization and to take initiative in consider the economic impact of their decisions.

2. Encourage people to look beyond their immediate surroundings

"You need to look beyond the immediate when considering consequences." Such a simple idea that is the root of all thinking in organizations: it's not about your interaction, it's about the team. It's not about your department, it's about the company. it's not about the company, it's about the ecosystem. Systems thinking does not tell you which level you should consider at any decision, just that you're probably looking at it too closely.

3. Allow your people to react to changing conditions

The SAFe principle of "assuming variability" means that you don't want to stop everything and start over when your inputs vary or if the requirements change over time. In knowledge work, you often don't want to create the exact same thing as before, so you shouldn't aspire to the same predictability of process as a chemical plant. To fully take advantage over this, people should be encouraged not to nail things down before they have to under perceived pressure to "get things done".

4. Insist on completing small things to foster learning

The most commonly recognized aspect of Agile is completing large undertakings through small tasks. There are a number of advantages to this approach but to foster learning and a sense of agency, completing small things allows your people to get early feedback on their whole process from end to finish - not just the early planning phases. When iterations go through all phases of delivery, you are not only able to iterate to improve the product, but also allow people to iterate on their process and practices.

5. Set milestones on value delivered

Don't set milestones based on your preconception about how the phases a solution will be developed in. Instead, insist that every iteration be made as a viable solution and measure progress in terms of value delivered - whatever definition of value fits your solution. The team will find the best way to make headway and stakeholders can be involved over the course of development.

6. Visualize everything

Visualizing helps your team focus, handle stress and understand how they work. Increasing flow by setting WIP limits, reducing batch sizes and managing queue lengths is important and useful, but up-to-date visualizations help your team understand what they are doing. Most importantly, the key driver of stress is often not working too hard, it's working with too little visibility.

7. Structure work to build routine and collaboration

SAFe is literally "Agile, but scaled". This is most apparent in teams working in parallel to one another but also in how work is anticipated over "scaled-up" (i.e. long) stretches of time. Having all teams working on cadence creates routines that buffer uncertainty: "'When do we overview work across team?' 'Next IP sprint, in 4 weeks.'" Having all teams and even teams of teams work on the same cadence creates opportunities for cross-team collaboration and problem-solving.

8. Unlock the intrinsic motivation of knowledge workers

This I didn't have rephrase at all, which makes me even more confident that SAFe has empowerment and respect for people built deep into its core. Instead of monetary incentives to exert control over your team, understand that the teams are already motivated. You only need to overcome the obstacles to their sense of autonomy, mastery and purpose. In best case, you can communicate a clear intention that your teams can pursue under minimal constraints. Good things come to those who allow.

9. Make less decisions

Once you have established and communicated a shared method of evaluating decisions (principle 1) in a system with maximum visibility (principle 2) and awareness (principle 6) where your people can adjust for changing conditions (principle 3), you are the last person who should be making any decisions for these people. And you won't.